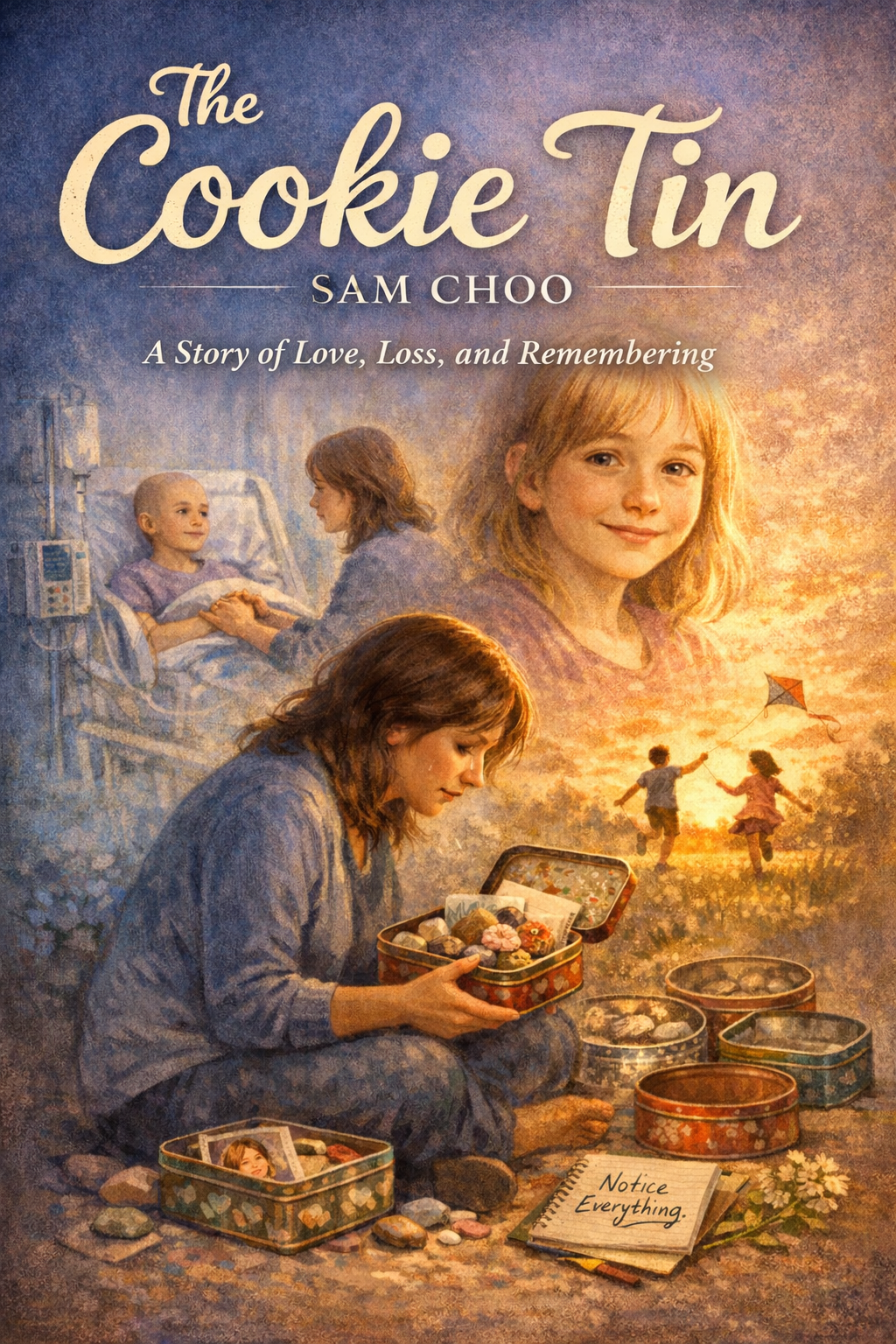

The Cookie Tin

Three months after she died, I finally opened the cabinet under the bathroom sink.

I had been avoiding it because I knew what was inside. Forty-seven bottles of lotion, lined up in uneven rows. Each one bought with hope. Each one tried once or twice and abandoned when it didn’t help. When the chemotherapy made her skin crack and bleed, we kept searching for something gentler. Something that would work.

I sat on the bathroom floor and opened every bottle.

I smelled them one by one.

This one, she said, smelled like sad flowers.

This one smelled like sunshine trying too hard.

The vanilla one made her smile. “At least I’ll be delicious,” she said.

My daughter was eleven years and sixteen days old when she died.

She had always noticed things other people missed. At five, she collected smooth pebbles “for people who need something to hold when they’re worried.” At eight, she started leaving notes in library books. You’re going to love page 47. This character reminds me of you, whoever you are.

When the diagnosis came, the words felt unreal and final at the same time. Stage IV neuroblastoma.

She asked one question.

“So how much time do I get?”

The oncologist said maybe a year with treatment.

She nodded. She pulled out the small notebook she always carried and wrote: 365 days. Notice everything.

And she did.

During treatment, she filled that notebook with ordinary things. Morning light on the hospital window. The exact color of her nurse’s nail polish. “Mermaid scales,” she said. The sound of her little brother laughing in the hallway when he wasn’t allowed in on her bad days.

When she was too tired to write, she dictated.

“Mom, write this,” she said once. “When you gave me water, you fixed my hair without even thinking about it. Write that down. I want to remember.”

I didn’t understand what she was doing. I was focused on numbers and schedules and buying time. She was doing something else.

She was collecting moments.

Three months before she died, when it was clear the treatment wasn’t working, she started sorting her room.

Not packing. Curating.

“People keep everything when someone dies,” she said, folding a sweater. “Then it’s just sad stuff in boxes. I want to choose what you keep.”

She made neat piles.

“Give this away. Someone else should wear it.”

“Keep this. You gave it to me for my eighth birthday and you cried the happy kind.”

“Give this to Lucas. He liked this elephant more than I did anyway.”

I tried to stop her. I said it was too much. Too heavy.

She looked at me and said, gently, “I’m too tired for pretending.”

So I sat on the floor and watched my eleven-year-old daughter teach me how to let her go.

That was when she brought out the cookie tins.

She had always saved them. She used them to store treasures. She set them between us and said, “These are the important ones. Sit with me.”

She opened them one by one.

The first tin held every birthday card I had ever written her.

“You always write ‘Love, Mom,’” she said. “But it looks different every time. Look. This one from when I was six. Your writing is shaky because you were pregnant with Lucas. This one from when I was nine. It’s so neat because you told me you practiced.”

She smiled. “I like that you tried.”

The second tin held ticket stubs, receipts, a folded napkin.

“These are from our best days,” she said. “Not the big ones. The small ones.”

She took out the napkin.

“Remember when we got stuck in the rain and had hot chocolate? You let me get the fancy one with the candy cane even though it cost extra. You kept saying it was silly, but you were smiling.”

I had drawn a smiley face on the napkin.

She smoothed it flat. “I kept this.”

The third tin held rocks, leaves, a dried flower.

“Pretty things don’t have to last forever,” she said. “They’re still pretty.”

The fourth tin was empty.

“This one is yours,” she said. “For later. When you find something that makes you feel like you again. A ticket. A napkin. Anything. Put it in here so you remember that good stuff still happens.”

I was crying by then, trying to be quiet.

She looked at me. “It’s okay to cry. It’s okay to be sad forever if you need to. But you can’t stop noticing things. That’s my only rule.”

In her last week, she slept most of the time.

One afternoon, she woke and found me sitting beside her bed, watching her breathe.

“What are you noticing?” she whispered.

“The way your hand curls when you sleep,” I said. “You’ve done that since you were a baby.”

She smiled. “Good. Keep doing that.”

On her last day, barely awake, she squeezed my hand.

“The cookie tin,” she murmured. “You get it, right?”

“Yes,” I said.

She nodded. “You will.”

After she died, I couldn’t enter her room for a month.

When I finally did, I found another tin hidden in her closet.

Inside was a letter.

Dear Mom,

You’re going to think you messed up because you couldn’t fix me. But here’s what you did do.

You knew when I needed quiet and when I needed you to be silly.

You learned all the medicine names even though they were scary.

You slept in that uncomfortable chair 127 nights. I counted.

You still made Lucas’s lunches and went to his games.

You cried in the shower so I wouldn’t hear, but I heard anyway.

You read to me every night, even when I was too sleepy to listen.

Now you have to do the hard thing again. Keep living. Keep noticing. Fill your tin with proof that you’re still here and still finding good things.

I’m not in the cancer anymore. I’m in the moments. In every time you see something pretty and think I would have liked that. I’m in your noticing.

Don’t keep me in the sad stuff. Keep me in what you do next.

Love,

Emma

P.S. That thing where you fix people’s hair. Do that for other people. They need it.

That was two years ago.

I carry the empty tin in my purse now.

Inside is a napkin from a café where I cried and a stranger brought me more napkins without asking why. A smooth stone from the beach where I scattered some of her ashes. A ticket stub from my son’s school play, the first one after she died, when I managed to clap and mean it.

Every night, I open the tin and add something.

A leaf. A note. Proof that I’m still here.

People sometimes ask me how I survived losing her.

But she didn’t leave me unprepared.

She spent her last year teaching me how to notice what remains.

And I will not waste the lesson.

Author’s Note: This story is a work of fiction.